Introduction

This page describes the vertical organization of the atmosphere and why those layers are critical for flight planning and in-flight decisions. It focuses on the layers pilots most commonly use when interpreting soundings, forecasts, and reports: the planetary boundary layer, temperature inversions, wind shear zones, freezing-level transitions, and the tropopause.

Using vertical information (soundings, PIREPs, and upper-air analyses) helps you anticipate cloud bases and tops, identify likely icing layers, locate zones of turbulence or wind shear, and understand how surface conditions may differ from conditions aloft. The operational guidance in the Overview below explains how these layers affect clouds, precipitation, icing, and turbulence.

Overview

Weather vertical structure describes how temperature, moisture, and wind change with altitude and how those changes produce layers that control cloud formation, precipitation, icing, and turbulence. Key vertical features include the planetary boundary layer, temperature inversions, wind shear layers, freezing-level transitions, and the tropopause. Understanding these layers helps pilots anticipate cloud bases and tops, convective potential, where icing or clear-air turbulence is most likely, and how surface conditions may differ from conditions aloft.

Why it matters: Vertical gradients determine cloud type and coverage (shallow stratiform vs. deep convective), influence the depth and intensity of precipitation, set freezing levels that govern icing risk, and concentrate turbulence in shear zones or near the tropopause. Proper preflight planning and in-flight monitoring of vertical profiles (soundings, pilot reports, and onboard observations) reduce surprises and improve decision-making.

Pilot actions: Check sounding-derived cloud bases/tops, freezing level, wind shear, and stability indicators during preflight; plan altitudes to avoid expected icing layers and shear zones; use alternates and fuel reserves to allow for routing around deep convection or long icing layers; and monitor PIREPs, satellite, and radar for evolving vertical structure en route.

Boundary Layer

The planetary boundary layer (PBL) is the lowest part of the atmosphere directly influenced by the surface. Its depth varies diurnally and by terrain; during the day convection can deepen the PBL, raising cloud bases, while at night a shallow stable layer often suppresses low-level turbulence. Pilots should note PBL depth for takeoff/landing performance, low-level wind shear potential, and for anticipating morning fog or low stratus.

Pilot guidance: Use surface observations, low-level wind profiles, and diurnal forecasts to estimate PBL depth; expect stronger turbulence and mixing when PBL is deep and convective.

Temperature Inversions

Formation: Radiational cooling at night or warm advection aloft commonly produces inversions; subsidence from high-pressure systems also creates stable layers.

Signs: A sharp layer of clear air above low stratus or smoke, steady surface temperatures overnight, and forecasted low-level temperature profiles in upper-air data.

Operational impacts: Trapped moisture increases fog and low ceilings near the surface, while turbulence and shear can be concentrated near the inversion interface. Aircraft climb/descent performance may differ markedly when crossing an inversion.

Pilot actions: Expect sudden visibility and turbulence changes when crossing an inversion; use conservative descent profiles, monitor PIREPs, and plan alternates if low-level inversions persist near destination.

Wind Shear

Formation: Shear commonly forms where gradients in pressure or temperature exist — near fronts, jets, convective outflows, and over complex terrain. Low-level jets at night can also create strong low-level shear.

Signs: Sudden airspeed changes, rapid changes in groundspeed or drift during approach, and PIREPs reporting turbulence or sudden altitude loss/gain.

Operational impacts: Shear can produce hazardous downdrafts, rapid airspeed variations, and turbulent conditions that affect approach and climb performance. Mountainous areas may generate rotors and severe mechanical turbulence in lee waves.

Pilot actions: Follow manufacturer and training guidance for shear escape techniques; increase approach speeds where appropriate, be prepared for go-arounds, and avoid close proximity to convective outflow boundaries.

Freezing Levels

Formation: Freezing-level heights depend on large-scale temperature profiles and can vary significantly across regions and with frontal passages or diurnal heating.

Signs: Forecast freezing-level charts, temperature soundings, and reports of rime or mixed icing conditions at specific altitudes or on aircraft in the area.

Operational impacts: Icing risk increases where clouds contain supercooled liquid water below freezing levels. Multiple freezing levels complicate safe altitude selection because an aircraft may encounter alternate warm and cold layers.

Pilot actions: Use freezing-level forecasts, OAT reports from ATC/PIREPs, and vertical profile data to select altitudes that minimize exposure; if unavoidable, consider faster routing through thin layers, anti-ice/de-ice procedures, or diversion.

Tropopause

Formation: The tropopause is a dynamically maintained boundary where the atmospheric lapse rate changes sign; its altitude varies with latitude and synoptic conditions, generally higher in the tropics and lower at the poles.

Signs: Strong wind maxima (jets) around the tropopause level, sharp changes in temperature lapse rate in soundings, and PIREPs reporting clear-air turbulence near jet cores.

Operational impacts: Jet streams and tropopause-associated shear concentrate clear-air turbulence and can significantly affect groundspeed and fuel planning. Deep convection close to the tropopause may reach its top and produce overshooting tops and severe turbulence.

Pilot actions: Check jet stream charts and upper-air forecasts before cruise planning; avoid flight levels near expected jet cores when possible, and use PIREPs and SIGMETs to route around areas with reported turbulence.

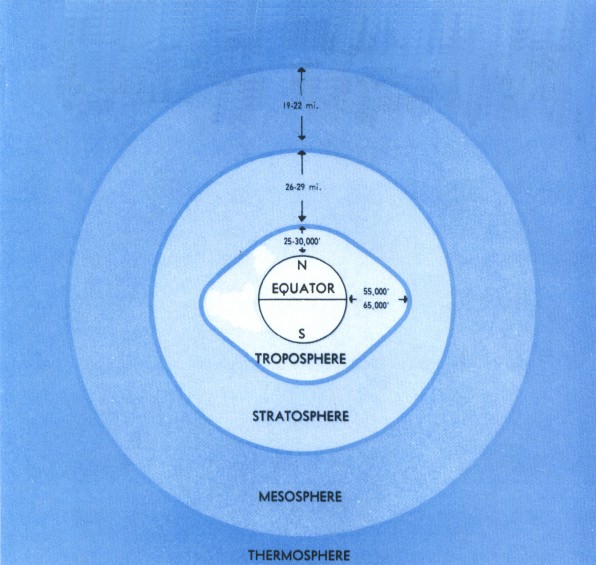

Troposphere

The troposphere is the lowest major layer of the atmosphere where nearly all weather occurs. Its thickness varies with latitude and season — typically about 8 km (roughly 26,000 ft) near the poles, ~11 km (36,000 ft) at mid-latitudes, and up to ~16–18 km (52,000–59,000 ft) in the tropics. The troposphere extends from the surface up to the tropopause and contains the vertical motions, moisture, and instabilities that produce clouds, precipitation, and convective storms.

Typical heights and flight levels: Tropospheric depth varies; common operational considerations are: low-level general aviation ops (surface to FL100), turboprops and regional jets (surface to FL250), and transcontinental/international turbine cruise (FL250–FL450) which may operate near the upper troposphere in some latitudes. Remember that the tropopause (top of the troposphere) is often the ceiling for convective development and sets the maximum storm top height.

Thermodynamics & instability: The troposphere's lapse rate (rate of temperature decrease with height) determines stability. Steep lapse rates and high surface-based CAPE (Convective Available Potential Energy) support deep convection and severe thunderstorms. Soundings showing large positive CAPE, steep low-level lapse rates, and strong low-level moisture indicate a high likelihood of towering cumulus and potential severe weather.

Clouds and hazards: Cumulus congestus and cumulonimbus are indicative of deep convective activity; widespread stratus indicates layered precipitation and low ceilings. Hazards within the troposphere include heavy precipitation, hail, icing in supercooled liquid layers, severe turbulence in convective updrafts/downdrafts and near shear zones, and low-level fog or low ceilings in stable boundary-layer situations.

Pilot actions: For tropospheric hazards, use soundings and model-derived freezing level charts to avoid prolonged exposure to icing layers; consult SIGMETs and radar for convective areas and plan routing/altitudes to remain clear of thunderstorm tops. When planning cruise altitudes, weigh headwind/tailwind, fuel, and turbulence forecasts — jet stream maxima near the tropopause can produce significant groundspeed changes and CAT (clear-air turbulence) near their cores.

Operational note: Always check recent radiosonde soundings, model forecast soundings, and PIREPs for cloud tops and freezing level variability along the route — the troposphere's vertical structure is the primary determinant of where aviation weather hazards will appear.

Stratosphere

The stratosphere lies above the troposphere and begins at the tropopause. Its vertical extent varies with latitude but commonly spans from the tropopause (~8–18 km depending on latitude) upward to approximately 50 km. The defining characteristic is a temperature inversion: instead of cooling with height, temperatures typically increase within the stratosphere because of ozone absorption of solar radiation. This produces much more stable conditions and very limited vertical mixing compared with the troposphere.

Signs and structure: Radiosonde soundings show a reversal of the lapse rate at the tropopause and low relative humidity above it. The lower stratosphere may still be influenced by upper-level jets and tropopause-level disturbances; wind maxima (jet streams) often sit near the tropopause and can extend into the lowermost stratosphere during certain synoptic setups.

Operational impacts and hazards: Because it is largely dry and stable, the stratosphere rarely produces the convective clouds and precipitation common to the troposphere, and icing is generally not a concern there. However, the tropopause/stratosphere interface is a frequent location of clear-air turbulence (CAT), especially near jet cores and sharp wind/shear gradients. Rapid wind changes with altitude (shear) around the tropopause can affect fuel planning, groundspeed, and passenger comfort.

Pilot guidance: For high-altitude operations, plan altitudes with awareness of jet-stream positions and CAT forecasts; consult SIGMETs and PIREPs for CAT near jet cores. Expect low humidity and negligible icing risk in the stratosphere, but remain alert for turbulence near the tropopause. High-altitude route planning should also consider wind maxima for fuel and time optimization — tailwinds can be exploited while headwinds should be avoided when practical.

Pilot actions: For high-altitude operations, consult upper-air charts and jet stream forecasts; expect limited weather development in the stratosphere but be alert for CAT associated with jet cores and tropopause-level shear. Note that icing is not a concern in the dry, warmer stratospheric layers, but structural considerations (e.g., turbulence) remain important.

Mesosphere

The mesosphere sits above the stratosphere and is characterized by decreasing temperature with height and very low air density. It is the region where most meteors burn up and where atmospheric tides and planetary waves can occur. The mesosphere is remote from aviation operations and is primarily of interest in atmospheric science rather than routine flight planning.

Signs and structure: Soundings rarely extend into the mesosphere in routine operational products; research soundings and satellite retrievals show very low densities, cold temperatures at the mesopause, and complex wave activity.

Operational impacts: The mesosphere has virtually no direct impact on routine aviation because it lies well above typical flight levels. High-altitude atmospheric phenomena originating in lower layers may have indirect influences on long-term climate patterns but are not used for tactical flight planning.

Pilot guidance: No direct operational actions are typically required for the mesosphere; continue to focus on tropospheric and lower-stratospheric information for flight decisions.

Thermosphere

The thermosphere begins above the mesosphere and extends into very high altitudes where solar radiation causes significant ionization of the atmosphere. Temperatures increase with altitude in this layer, and it hosts the ionosphere — the region important for long-range radio propagation and satellite drag.

Signs and structure: The thermosphere is characterized by very low densities and high-energy solar radiation effects. Its properties vary with solar activity, time of day, and geomagnetic conditions; operational monitoring typically relies on space weather products rather than in situ soundings.

Operational impacts: Although the thermosphere is well above any aircraft operating altitudes, ionospheric conditions in the lower thermosphere affect HF radio propagation, satellite communications, GNSS accuracy, and space weather hazards. Periods of strong solar activity can degrade communications and navigation services used by aircraft on polar or oceanic routes.

Pilot guidance: For polar and long-range flights, monitor NOTAMs and space-weather advisories; plan alternative communication paths if HF or satellite comms are degraded, and be aware that GNSS performance may be affected during geomagnetic storms.

Exosphere

The exosphere is the outermost layer of Earth's atmosphere where particles are so sparse that they can travel hundreds of kilometers without colliding. It transitions gradually into outer space and does not participate in the meteorological processes that affect aviation.

Operational impacts: The exosphere has no direct effects on aircraft operations. It is relevant to orbital mechanics, satellite decay, and space mission planning rather than routine flight planning.

Pilot guidance: None — continue to use tropospheric and lower-atmosphere products for operational decisions. Space operators and satellite mission planners work with exospheric models when necessary.

Learn More

Resources for analyzing vertical structure: soundings, upper-air products, jet streams, freezing-levels, and space weather.

- Aviation Weather Center (AWC) — Official NWS aviation forecasts, SIGMETs, and upper-air guidance.

- University of Wyoming Soundings — Interactive radiosonde plots and sounding archives for cloud, stability, and freezing-level analysis.

- NOAA JetStream — Educational material on jet streams, tropopause, and upper-level dynamics.

- NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) — Space weather alerts and forecasts that affect HF and GNSS.

- NOAA NCEI Data Access — Upper-air datasets and archives for research and operational verification.

- AWC ADDS (Graphical Products) — Freezing level charts, model-derived vertical profiles, and graphical upper-air products.